Debate participants push for more subtle UK approach to CCUS risks

A UK-focused industry debate following the release of a report on prospects for carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) has highlighted how CCUS project costs are still rising and the UK government needs to get a better handle on the role it must play to better manage risks. The consensus among participants was that more subtle mechanisms were needed to deliver what’s needed for the long term.

The remarks were made in a freewheeling discussion following the release of a new report on driving cost reductions and value for money from the Carbon Capture and Storage Association (CCSA), which is a UK-based industry association for accelerating the commercial deployment of CCUS.

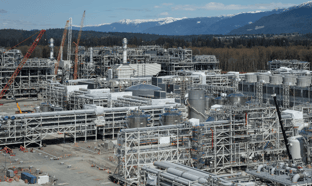

David Parkin, Director at UK-based low-carbon project developer Progressive Energy, said industrial carbon capture models were complex and relatively untested and had seen significant cost escalation over the past five years.

“There are lots of reasons [for this],” said Parkin. “We’ve seen high inflation and inevitably a level of optimism bias … [in] a competitive process. When some of these bids were submitted early on, there were relatively small amounts of development capital allocated, and only when they’ve got certainty on the process have they spent more.”

... to continue reading you must be subscribed